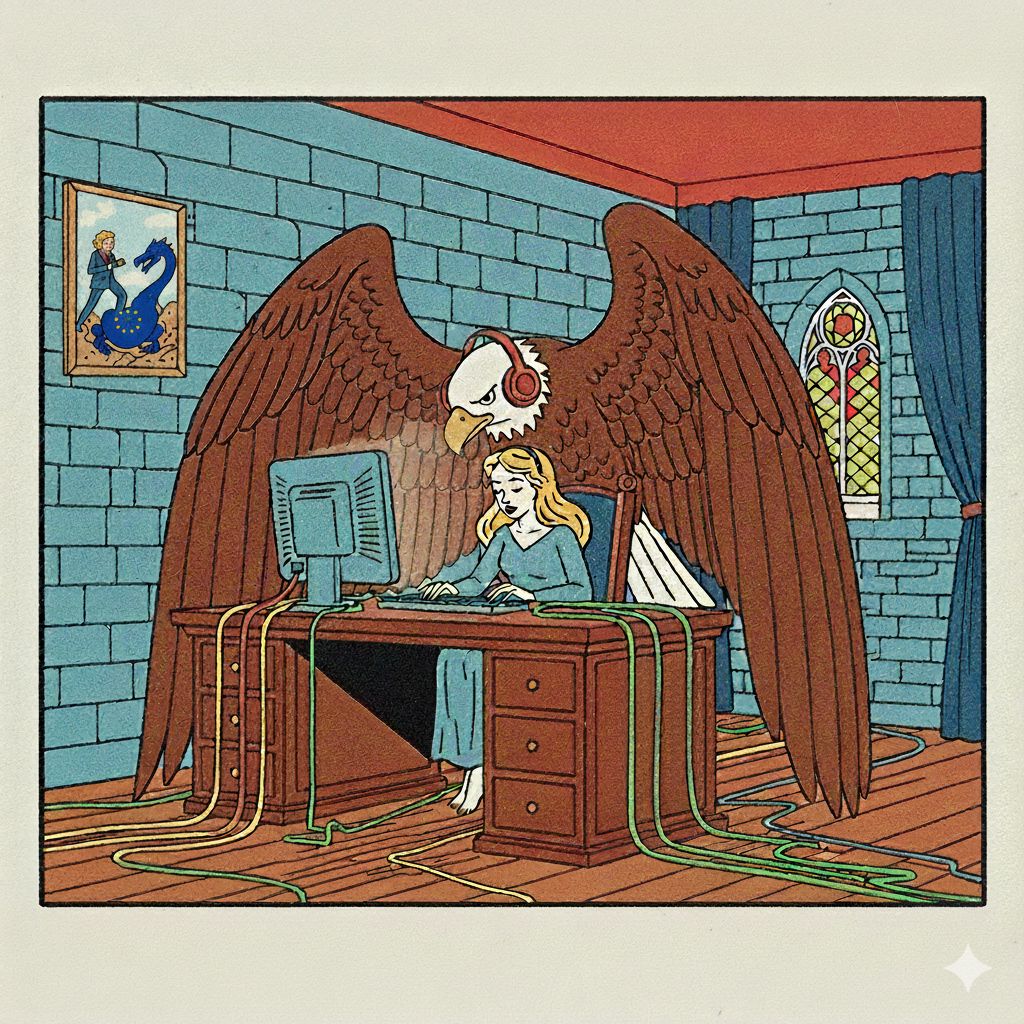

This article is part of a series: The journey of a file - The risk of US access.

- Introduction

- Part 1: Internet Network & Hardware and OS

- Part 2: Company network & Identity

- Part 3: Cloud storage & Encryption certificates (Comming Soon)

- Part 4: Transfer service infrastructure & Browsers (Comming Soon)

- Part 5: AI, automation, metrics & Corporate ownership (Comming Soon)

In this part of our series we have a look at the next two transit points: company networks/remote workspaces and the identity access layer.

Transit point 2: Networks/remote workspaces

The shift toward hybrid work has fundamentally changed how corporate data moves, making the network and remote workspace layer a critical transit point for sensitive information.

Today, organizations primarily rely on two technological frameworks to facilitate remote access: Virtual Desktop Infrastructure (VDI) and Virtual Private Networks (VPNs). While these solutions are often used in combination, they are based on distinct architectures and introduce different jurisdictional and operational risk profiles.

In a VDI environment (using platforms such as Citrix Workspace, VMware Horizon or Microsoft Remote Desktop Services) applications and data typically remain within a centralized data center or cloud environment. The user’s local device functions primarily as a terminal, receiving a rendered session rather than processing data locally. By contrast, a VPN establishes an encrypted tunnel that allows a remote device to connect directly to the corporate network. Under this model, data is more frequently accessed, stored, or processed on the employee’s local machine. While VDI is often preferred for its ability to centralize data, both approaches rely heavily on vendor-controlled infrastructure and software layers.

This reliance creates a structural exposure to international legal reach. Many dominant VDI and VPN providers are headquartered in the United States and are therefore subject to US legal frameworks such as the CLOUD Act and Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA). Under these regimes, US authorities can compel service providers to provide access to data under their control, including data associated with non-US customers and, in some cases, data processed or managed outside the United States.

The scope of such access may extend beyond content to include metadata and operational logs, such as connection timestamps, user identifiers, and session characteristics. In managed VDI environments, providers may retain visibility into parts of the management or control plane, which can reveal organizational structures, access patterns, and workflow dependencies. While this does not imply routine inspection, it introduces a jurisdictional exposure that may be invisible to the customer organization.

Operational continuity presents a related but distinct risk. Modern remote workspace platforms increasingly depend on cloud-verified licenses, identity services, and periodic validation checks with vendor infrastructure. This design gives providers the technical ability to suspend or terminate services in response to legal, contractual, or policy changes. Recent geopolitical developments and sanctions regimes have demonstrated that software access and licenses can be revoked at short notice. For European organizations, this creates a non-theoretical risk that remote work capabilities could be disrupted due to decisions taken outside their legal or political control.

Market consolidation

These concerns are compounded by significant market consolidation. Many VPN and remote access brands operate under shared ownership structures, despite presenting themselves as independent services.This consolidation can enable internal data sharing between subsidiaries and parent companies under broader corporate privacy policies. In some cases, ownership overlaps between service providers and review or comparison platforms further complicate independent risk assessment.

In conclusion, as remote access becomes a permanent component of the corporate environment, the choice of network and workspace layer is no longer purely technical. Organizations must balance usability and scale against jurisdictional exposure and dependency on foreign-controlled infrastructure. Assessing provider ownership, legal obligations, and architectural control points is essential for maintaining digital sovereignty in a hybrid work context.

European alternatives

As concerns around jurisdiction, transparency, and long-term control grow, a diverse European ecosystem has emerged across VPN, VDI, and remote workspace technologies. Rather than relying on a small number of U.S.-based hyperscalers, European organizations increasingly turn to providers that operate under EU or closely aligned legal frameworks, emphasize strict no-logs policies, and maintain transparent ownership structures.

1. European VPN Alternatives

European VPN providers such as Mullvad (Sweden), Proton VPN (Switzerland), IVPN (Gibraltar/EU), and AirVPN (Italy) exemplify this approach. While differing in technical implementation, these providers share common principles: minimizing data collection, operating under strong European privacy regimes, and publicly committing to transparency through audits, open documentation, or activist-driven governance models. Together, they illustrate that privacy-preserving network transit can be delivered without dependency on U.S. or Chinese infrastructure.

2. European VDI & Remote Workspace Alternatives

The landscape for Virtual Desktop Infrastructure (VDI) and remote workspaces is more complex, as these systems require substantial backend infrastructure and tight integration with enterprise environments. Nonetheless, several European-based providers offer sovereign or regionally controlled alternatives to dominant US platforms such as Microsoft and Citrix. Solutions from companies like UDS Enterprise, OVHcloud, T-Systems, and Scaleway illustrate a growing market for European-owned VDI and remote desktop offerings. These platforms are typically positioned around “sovereign cloud” principles, ensuring that software development, hosting infrastructure, administrative access, and legal accountability remain within European borders. For regulated industries and public-sector organizations in particular, such solutions offer a way to maintain remote work capabilities while aligning with European data-residency and governance requirements.

3. Open-Source and Self-Hosted Options

For organizations seeking the highest degree of control, open-source and self-hosted solutions provide an additional path toward digital sovereignty. Technologies such as WireGuard enable enterprises to deploy high-performance VPN infrastructure entirely on their own hardware, eliminating reliance on third-party transit providers. Similarly, platforms like Nextcloud Hub demonstrate how collaboration and productivity environments can be operated as locally hosted, European-controlled alternatives to US-based SaaS ecosystems. While these approaches demand greater operational maturity, they significantly reduce dependency on external vendors and remove the risk of unilateral service withdrawal or extraterritorial legal interference.

European law proposals (with VPN impact)

However, this risk is no longer confined to the US context. In parallel, European and UK policymakers are reassessing the role of anonymity, encrypted transport layers, and location-obscuring technologies within new safety, law-enforcement, and identity frameworks. While the legal logic differs, recent developments suggest a growing willingness in Europe to assert regulatory control over the same network layers that are often assumed to be structurally sovereign.

VPNs, long positioned as tools for privacy and security, are increasingly viewed by policymakers as technologies that can undermine new online safety and enforcement regimes. While neither the UK nor the EU has introduced an outright ban, both are developing legal frameworks that could significantly affect the operation of “no-log” VPN services.

United Kingdom: Online Safety and Age Assurance

In the UK, regulatory attention is largely driven by enforcement of the Online Safety Act (OSA). Since the introduction of mandatory age verification requirements for certain online services in 2025, authorities have reported a substantial increase in VPN usage, particularly around enforcement periods. Regulators interpret this trend as evidence that some users are using VPNs to bypass location-based age assurance mechanisms.

In response, Ofcom has expanded its monitoring and evidence-gathering activities, drawing on traffic analysis, platform data, and third-party market intelligence. A report examining the interaction between VPN usage and the effectiveness of age assurance measures is expected in May 2026, followed by a broader review later in the year.

Alongside this, legislative attention has turned to the Children’s Wellbeing and Schools Bill. Amendments proposed in late 2025 would require VPN providers operating in the UK to implement “highly effective” age assurance measures. In practice, this could mean identity or age verification before VPN services can be accessed. While the government has stated that it is not pursuing a general ban on VPNs, it has warned that services actively promoting VPN use to circumvent UK law could face enforcement action.

European Union: Metadata Access and Anonymity

In the EU, the regulatory focus is broader and more structural. As part of the ProtectEU internal security strategy, the European Commission’s June 2025 roadmap includes data retention as a key area for reform, with an impact assessment completed and a legislative proposal expected around mid-2026. This proposal would require certain digital service providers (including VPNs) to retain traffic and location metadata for law-enforcement purposes. If adopted, this would be incompatible with strict “no-log” operating models.

At the same time, negotiations on the Child Sexual Abuse Regulation (CSAR) have continued into 2026. While earlier proposals for mandatory scanning of encrypted communications were softened, the current approach emphasizes risk mitigation. VPNs are increasingly discussed as services that may fall into higher-risk categories, potentially leading to additional obligations to support lawful investigations.

In parallel, the EU is preparing for the rollout of the European Digital Identity Wallet, which member states must make available by the end of 2026. The Commission positions the wallet as a standardized mechanism for identity and age verification. Its broader adoption could reduce reliance on location-based workarounds, while also making anonymous access to online services more difficult to sustain.

Conclusion

For VPN providers, 2026 marks a period of strategic uncertainty rather than immediate prohibition. Both the UK and the EU are moving toward regulatory models that emphasize age assurance, traceability, and lawful access to metadata. These developments do not eliminate VPNs, but they do challenge privacy-maximizing designs, particularly “no-log” architectures. Providers operating in these jurisdictions may increasingly face a choice between adapting to verification and retention requirements or limiting their services geographically.

Example 1: FBI operation against VoltTyphoon botnet

A clear real-world example of network-layer intervention by U.S. authorities is the 2023–2024 Volt Typhoon case, in which the FBI, under a December 2023 secret court-authorized warrant issued by a federal magistrate in Texas, remotely accessed and cleaned malware from hundreds of Cisco and Netgear home and small-office routers infected with the KV Botnet. The malware had been used by Chinese state-linked hackers to disguise and relay intrusions into U.S. critical infrastructure.

In this operation, the FBI deleted the malicious code and blocked its communications with the botnet’s control servers without the consent of the device owners, relying on the court order to make the action legal.

While the stated intention was to protect citizens and U.S. infrastructure from foreign malware, the case also highlights the broader authority that U.S. government and intelligence agencies can wield at the network layer and effectively reaching into private network devices to modify or remove software.

Expanding legal definition

This authority was based on an expansion of Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 41, which traditionally governs search and seizure warrants; critics argue that using a criminal warrant to authorize nationwide hacking stretches the original legal framework, since Rule 41 was designed for probable-cause searches of individual devices, not mass remote access.

The concern is that if such warrants can be used to justify broad interventions into networked devices, the same legal theory could, in principle, be applied far beyond serious national-security threats, raising questions about scope, oversight, and civil liberties.

Example 2: SolarWinds Supply-Chain Attack (2020–2021)

A prominent example illustrating the interaction between the network layer and the access layer is the SolarWinds supply-chain attack, publicly disclosed in late 2020 and investigated throughout 2021. SolarWinds’ Orion platform functions as network-monitoring software deeply embedded in enterprise IT infrastructures, providing visibility, authentication support, and automated patching across internal networks and cloud environments.

By compromising SolarWinds’ software update mechanism, the threat actor inserted malicious code that was digitally signed and distributed to thousands of customers, granting trusted network-level access inside government agencies and private companies worldwide. Once inside, the attackers exploited systemic weaknesses in Windows authentication and identity federation, allowing lateral movement across internal networks and into cloud environments while bypassing multifactor authentication, effectively collapsing the boundary between network trust and access control.

Transparency hesitation

Despite the unprecedented scale and severity of the breach, post-incident investigations revealed hesitancy among some organizations to fully disclose details of the intrusion. Witnesses later cited concerns about legal liability and the risk of “victimizing victims” by publicly naming affected entities. This reluctance persisted even though the Cybersecurity Information Sharing Act (CISA) of 2015 explicitly provides liability protections to encourage companies to share cyber-threat indicators and defensive measures with government agencies and other firms, provided that sharing follows statutory protocols. The SolarWinds case therefore highlights not only technical vulnerabilities at the network and access layers, but also institutional and legal frictions that can limit transparency, even when legal frameworks are designed to promote it.

Duality

This SolarWinds incident highlights that private companies operating critical infrastructure software are not always fully transparent about breaches, even when legal frameworks such as the Cybersecurity Information Sharing Act (CISA) exist to encourage disclosure. Because companies may withhold information, there are risks to broader network security, and political or regulatory pressures could be used to further incentivize or legally obligate transparency.

This dynamic creates a duality: expanding governmental access and influence can help detect intrusions, mitigate systemic cybersecurity risks, and protect both public and private actors from sophisticated state-sponsored attacks, but it also introduces potential downsides.

Greater technical and legal reach by the U.S. government can expose European companies and citizens reliant on U.S.-based technology and cloud infrastructure, to jurisdictional and political risks, highlighting the tension between security benefits and concerns over sovereignty, oversight, and unintended exposure.

Transit Point 3: Identity & Access Management (IAM)

Moving deeper into the architecture of modern digital ecosystems, we arrive at Transit Point 3: the IAM Layer. If the first transit points of our file that we are following represents physical and network infrastructure, this IAM transit point serves as the critical gatekeeper: the intelligent filter that determines not just who a user is, but exactly what they are permitted to do once they cross the threshold. In an era where identity is the new perimeter, IAM has become a primary defense against data breaches, as it is far easier for a malicious actor to steal a credential than to bypass a firewall.

In business contexts, IAM is the “connective tissue” between a digital presence and operational security. It governs every interaction between humans or machines and corporate resources: from a remote employee logging into a VPN to a customer subscribing to a SaaS service. At its core, IAM authentication ensures the right entities have access to the right resources at the right time for the right reasons.

Authentication Methods and Risks

To reduce friction for users, organizations increasingly adopt Single Sign-On (SSO) and social logins (e.g., “Sign in with Google” or “Login with Facebook”). While these solutions simplify access and improve conversion rates, they introduce a systemic risk: the “master key” problem. If a user’s primary social or SSO account is compromised, the breach propagates across all connected services.

Password-based IAM remains widespread, but many users reuse weak or non-unique passwords and fail to enable two-factor authentication. To mitigate these risks, modern IAM frameworks integrate secondary verification methods such as biometrics, time-based one-time passwords (OTP), and physical hardware tokens (like YubiKeys). These additional layers help prevent a compromised password from granting unrestricted access.

Increasingly, organizations are adopting passkeys, which replace shared secrets with device-bound, asymmetric cryptographic credentials. Passkeys authenticate users through a private key stored locally on the device, often unlocked with biometrics or a PIN. This eliminates the need for passwords and significantly reduces exposure to phishing and credential reuse. However, in practice, passkeys ecosystems are tightly integrated on platform-managed synchronization and recovery services (Apple, Google, Microsoft), introducing dependencies outside the organization’s control. While avoiding traditional key escrow, these services create a de facto escrow-like dependency and concentrate trust in foreign cloud providers.

Intermediaries and Platform Dependencies

Password managers increasingly function as a critical intermediary, storing high-entropy passwords or managing passkey private keys across devices. While they improve usability and security, they also concentrate trust in a single custody point. Many widely used solutions are US-based, relying on cloud synchronization services subject to US jurisdiction. Even with end-to-end encryption, metadata and recovery mechanisms may fall outside European control. Organizations can reduce this dependency using European-based or self-hosted password managers (e.g., Proton Pass, Bitwarden self-hosted, KeePass-based enterprise integrations), maintaining control over key custody and infrastructure.

Similarly, most enterprises now rely on IAM/Identity-as-a-Service (IDaaS) providers rather than building authentication systems in-house. Leading platforms like Okta, Auth0, and Microsoft Entra ID offer scalability and robust security features but are predominantly US-based, placing them under US jurisdiction. This creates legal tension for European companies: US authorities may compel data disclosure even when data is stored physically in Europe, potentially conflicting with GDPR and local sovereignty obligations. Outsourcing identity management to social login or IDaaS providers also means ceding control over a core security layer. The provider’s business objectives may not align with a company’s risk management or privacy policies, further highlighting the need for careful evaluation.

European Alternatives

To address these challenges, a new generation of European IAM solutions has emerged, including Forgerock, Corma, and Zitadel (we use self-hosted Zitadel in our Databeamer application). Many are built on open-source foundations and support on-premises deployment or hosting within European cloud environments. Choosing such providers is a strategic decision to de-risk the identity layer, retain auditability, ensure compliance with European privacy law, and protect against foreign jurisdictional reach.

The European Digital Identity Wallet

Looking ahead, identity at our Transit point 2 is expanding beyond corporate environments into the public domain with the introduction of the European Digital Identity Wallet. Enabled by the eIDAS 2.0 regulation, this initiative reflects the European Union’s effort to strengthen digital sovereignty by providing every EU citizen and resident with a secure mobile based identity that is recognized across all 27 member states. The wallet is designed as a unified digital container that can hold a wide range of verified attributes, including identity documents, driving licenses, academic credentials, bank account information, and medical prescriptions.

From a business perspective, the EUDI Wallet significantly reduces cross border friction. Use of the wallet is free and voluntary for citizens, and physical identity documents remain valid. For the private sector, however, adoption is mandatory. Very large online platforms and providers of essential services such as banking, energy, and transport will be required to accept the wallet for authentication. This establishes a standardized and high assurance trust layer that reduces reliance on custom verification solutions or weaker social login mechanisms.

For citizens, the primary benefit lies in selective disclosure. Instead of revealing full identity details when proving eligibility, users can confirm specific attributes such as age or license validity without sharing additional personal data. This privacy by design model shifts control back to the individual and moves away from data driven identity models toward one where the user retains ownership of their identity information.

Despite these benefits, the move toward a centralized digital identity also introduces significant risks. From a citizen perspective, a key concern is the creation of a single point of failure. If a smartphone is compromised or the wallet infrastructure is breached, a wide range of legal, financial, and educational information could be exposed. There are also persistent concerns about state surveillance and tracking. Although the regulation states that the wallet cannot be used to monitor daily activities, critics warn that metadata related to when and where the wallet is used could still enable detailed profiling over time. In addition, there is a risk of digital exclusion. As the wallet becomes a standard method for accessing services such as transportation, rentals, or public benefits, individuals who lack digital skills or choose not to participate may face reduced access to essential services.

In a broader context, the EUDI Wallet can be seen as the natural culmination of Layer 2, shifting digital identity away from private US based intermediaries and into a regulated European framework. While no system is without risk, the European model is grounded in democratic oversight, legal transparency, and a balance of powers across multiple national governments and institutions. This provides stronger checks and accountability than identity infrastructures governed by a single foreign jurisdiction. As a result, the EUDI Wallet aligns with a wider movement toward sovereignty by design, where identity is treated not as a commercial asset, but as a public good and a fundamental right deserving of long term protection.

Conclusion

The IAM Layer is a cornerstone of modern cybersecurity, balancing usability, security, and regulatory compliance. Strong authentication methods, device-bound credentials, and careful provider selection are essential to protect against credential compromise, phishing, and lateral movement across networks. At the same time, reliance on cloud and platform providers introduces dependencies and jurisdictional considerations that European organizations must manage strategically. Choosing self-hosted or European-based IAM solutions ensures greater control over infrastructure, identity governance, and compliance, making the IAM Layer both a functional and legal safeguard in modern digital ecosystems.

Examples transit point 3 IAM

In practice, identity and access management (IAM) systems are seldom the direct trigger for government intervention or service disruption. Rather, they function as the enforcement layer through which legal mandates, court orders, or national security directives are executed. IAM platforms provide the mechanisms to grant, restrict, or revoke access in response to external legal obligations, making them a critical point of control once a decision has been taken elsewhere.

Within this broader IAM landscape, privileged access management (PAM) plays a particularly important role. Many incidents involving misuse or unauthorized access underscore the need to tightly control, monitor, and audit highly privileged accounts, which have the ability to access sensitive systems and data across an organization. PAM is therefore essential not only for reducing insider risk, but also for ensuring accountability when elevated access is required.

Robust auditing and logging capabilities are another foundational aspect of IAM. Detailed records of who accessed which resources, at what time, and from which location are central to regulatory compliance, forensic investigation, and the detection of anomalous behavior. While such logging does not eliminate all forms of misuse, it provides the visibility necessary to assess risk and respond effectively when issues arise.

Finally, IAM systems operate within a broader socio-technical context. Even well-designed access controls can be challenged by human factors, including social engineering, exploitation of previously unknown vulnerabilities, or deliberate circumvention by trusted insiders. As a result, IAM should be understood not as a standalone safeguard, but as one component of a layered security and governance strategy.

Example 1: ICC Sanctions

For example, when the United States imposed sanctions on the International Criminal Court in 2025 after it issued arrest warrants for Israeli leaders, those legal measures had immediate practical consequences that went beyond traditional diplomatic pressure. The ICC’s Chief Prosecutor, Karim Khan, saw his official email account with Microsoft suspended and his bank accounts frozen as a result of the sanctions, and he lost access to standard communication and financial services linked to U.S. infrastructure.

Canadian ICC judge Kimberly Prost reportedly lost access to her credit cards and even saw consumer services like Amazon’s Alexa stop responding because of her inclusion on the sanctions list, illustrating how legal actions by a foreign government can disrupt everyday digital access when identity and access services are controlled within that legal jurisdiction.

These outcomes stem from reliance on U.S.-based platforms and financial systems, and demonstrate how, in a world where identity and access are deeply integrated with major cloud and service providers, government-mandated legal access or blocking of accounts can have sweeping effects on individuals’ ability to function professionally and personally.

Example 2: Slack’s sanctions‑related account blocks In another real‑world

case highlighting the geopolitical risks of relying on foreign‑controlled identity and access systems, the workplace communication platform Slack implemented sweeping account blocks in late 2018 to comply with U.S. sanctions against Iran. In an effort to align with U.S. trade embargoes and export control regulations, Slack’s automated compliance changes led to the deactivation of accounts tied (via geolocation data) to Iran and other sanctioned regions, even when those users were located elsewhere or had only briefly visited those countries.

Affected individuals suddenly lost access to their accounts, messages, channels, and files without prior notice, disrupting collaboration and digital life. Slack later apologized, acknowledged that it had mistakenly deactivated many accounts, and restored access in most cases, but the incident underscores how legal mandates tied to a provider’s jurisdiction can translate into abrupt, far‑reaching service interruptions for individuals around the world.