This article is part of a series: The journey of a file - The risk of US access.

- Introduction

- Part 1: Internet Network & Hardware and OS

- Part 2: Company network & Identity

- Part 3: Cloud storage & Encryption certificates (Comming Soon)

- Part 4: Transfer service infrastructure & Browsers (Comming Soon)

- Part 5: AI, automation, metrics & Corporate ownership (Comming Soon)

Transit point 0: Internet Network

Every standard online activity, from sending an email to transferring a large file, relies on the physical infrastructure of the internet known as the backbone. Historically, this hierarchy was dominated by Tier-1 networks: the “highways” of the internet that exchange massive volumes of traffic without charging each other fees (settlement-free peering). While American providers like Lumen and AT&T have always been prominent, Europe has maintained significant digital sovereignty through its own independent Tier-1 players like Deutsche Telekom and Arelion. Next to these global internet backbone Internet Service Providers (ISP’s), also regional and national carries (tier 2) and local providers (tier 3) exists.

However, a massive shift has occurred in recent years. Major “Hyperscalers” like Google, Meta, Amazon, and Microsoft have evolved from being customers of the internet to becoming the owners of its core. By 2025, these companies own or control roughly half of the world’s submarine cables, creating a private “Tier 0” backbone. Instead of using the public Tier-1 highways, they often link their data centers directly to local ISPs. This effectively flattens the internet, allowing data to move through private corporate networks that operate under their own internal policies rather than public standards.

It is not an entirely negative scenario, as these new routes introduce greater resilience and more standardization. However, the level of control they represent also raises concerns, particularly around data security and the risk of disruptions.

This shift complicates how your data travels. The path is determined by the Border Gateway Protocol (BGP), which acts as the internet’s global GPS. While BGP typically attempts to keep European traffic within the region to ensure speed, routing is ultimately a business decision. If a US-owned backbone offers a more efficient or cost-effective path, “local” traffic between two European cities there is always a chance that it traverse infrastructure controlled by American corporations.

This reality introduces distinct legal and even geopolitical risks. Under the US legal frameworks American agencies can issue orders to US-based companies to retrieve data moving through their networks, regardless of where that data is physically located.

Geopolitical risks

Geopolitical tension between US and China about the control over the undersea fiber-optic cable industry has significantly increased last years. In the early years of global telecommunications, cables were built primarily by private consortia to meet demand for faster and higher-capacity connectivity. But as China’s tech and industrial footprint grew, Beijing’s state-linked firms began investing heavily in manufacturing, maintaining, and even financing undersea cable projects. For the US and Europe, this shift triggered alarms about foreign access to critical communications infrastructure and potential intelligence collection.

The U.S. government, alarmed that Chinese involvement could create opportunities for espionage or influence over global traffic flows, has intervened in multiple cable projects. See also example 2 in this document. Through regulatory pressure, incentives, and diplomatic engagement, Washington has steered contracts toward American or allied firms and blocked or rerouted projects involving Chinese entities, especially where such cables touch U.S. territory.

Security analysts and lawmakers have raised concerns that foreign involvement in undersea cable manufacturing, repair, or maintenance could serve as a “backdoor” into data streams. Since cables extend far from national borders and much of the infrastructure is owned and operated by a patchwork of private companies, the risk is not just theoretical: if components or repair activities can be influenced by state actors, the potential for covert access or tampering increases.

Congressional inquiries have even asked major U.S. tech companies to disclose the extent of Chinese involvement in the cable systems they rely on, underscoring how deeply integrated these networks are with global commerce and national security.

Beyond surveillance, undersea cables are now viewed through a military and geopolitical lens. Recent incidents, from suspected cable cuts in the Baltic Sea to disruptions near Taiwan, highlight how vulnerable these networks are. Reports indicate that state actors, including those linked to Russia and China, may damage cables as part of gray zone tactics intended to disrupt or pressure rivals without triggering open conflict. On the other hand, China also accuses the US of engaging in subsea spying activities.

Taiwan, acutely aware that its global connectivity and even economic resilience depends on these undersea links, has intensified patrols around critical cable routes, reflecting how undersea infrastructure now occupies center stage in regional security planning.

European sovereign infrastructure

While the US is wary of Chinese espionage, Europe is becoming increasingly wary of US interventions. In response to US and China’s undersea dominance, Europe is increasingly pushing for sovereign clouds and infrastructure: infrastructures that are legally and physically confined within European jurisdiction to protect data from foreign intelligence orders. While a total “kill switch” scenario where Europe goes dark is unlikely due to the continent’s already robust internal redundancy, the vulnerability lies also in jurisdiction and surveillance.

While you as an individual cannot re-route global fiber-optic cables to ensure your messages and file transfers remain ‘untouched’, you can influence this landscape by staying alert to where your data lives, choosing privacy-first tools that prioritize local routing and encryption, and supporting political initiatives that advocate for digital sovereignty.

Examples transit point 0

Two examples illustrating how the U.S. government has exerted influence over this transit point 0 in the past.

Example 1: Operation Eikonal

An example from two decades ago shows that the German spy agency BND (Bundesnachrichtendienst) worked together with the American NSA (American National Security Agency) in Operation Eikonal. Here the BND worked together with Deutsche Telecom (DT), they literally placed a splitter on a fibre cable, and data about German telecommunication and therefore also German citizens was copied by the NSA for their own use. DT had their thoughts about this all, it seems that cooperation was not totally free will. This happened between 2004 and 2008.

In 2018, Frankfurt based DE-CIX, the world’s largest internet exchange point, revealed that Germany’s foreign intelligence service, the BND, had been intercepting and copying large volumes of internet traffic passing through its Frankfurt exchange since at least 2009. The practice, carried out under strategic surveillance authorities, was later ruled unlawful by Germany’s Federal Administrative Court, which found that the indiscriminate monitoring of traffic at DE-CIX exceeded the BND’s legal mandate.

Example 2. FISA 702 and “Upstream” Collection

While discussions about data privacy often focus on software, the most profound risks exist at the physical layer of the internet. A prime example of US governance exercising control over this infrastructure is the “Upstream” collection program conducted under Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA).

Unlike US programs that request data from a specific app or service provider, often called “downstream collection” or PRISM, upstream collection occurs at the level of the “internet backbone”. Based on this Act, US intelligence firms collected and intercepted a lot of private data without having legal warrants. These warrantless backdoor searches were ruled unconstitutional. Changes where made to this bill in April 2024, but it still provides legal means to check a persons communications and transferred files and also in upstream collection.

Under this authority, the US government (with the compelled assistance of telecommunications giants like AT&T and Verizon) collects data directly from the fiber-optic cables, switches, and routers that carry global internet traffic. This means that as data pulses through the physical cables at the bottom of the ocean or through major internet exchange points, it is subject to “filtering” by US intelligence agencies.

This is not merely a theoretical concern; it was the primary technical reality that led the Court of Justice of the European Union to strike down the Privacy Shield in the Schrems II ruling.

The court found that because the US government can tap into the physical infrastructure to scan traffic for “selectors” (such as email addresses or IP addresses) without a specific warrant for European citizens, the physical layer itself becomes a site of legal vulnerability.

Geopolitical Gatekeeping: The Pacific Light Cable Network

Beyond active surveillance, the US government also exercises “governance access” by dictating where the physical infrastructure is allowed to exist. In recent years, the “Team Telecom” committee (an inter-agency group including the Department of Justice and Defense) has blocked major subsea cable projects based on national security concerns.

A landmark case is the Pacific Light Cable Network (PLCN), a massive undersea fiber-optic link funded by Google and Meta. While the cable was intended to connect the US to Hong Kong, the US government intervened, forcing the companies to disable the Hong Kong portion of the cable and reroute it to Taiwan and the Philippines.

This demonstrated that this physical transit point 0 is not a neutral utility, but is also geopolitical tool. For a business, this means that even if your data is encrypted, the very path it takes across the globe is subject to the strategic interests and judicial reach of the US government, regardless of where your company is headquartered.

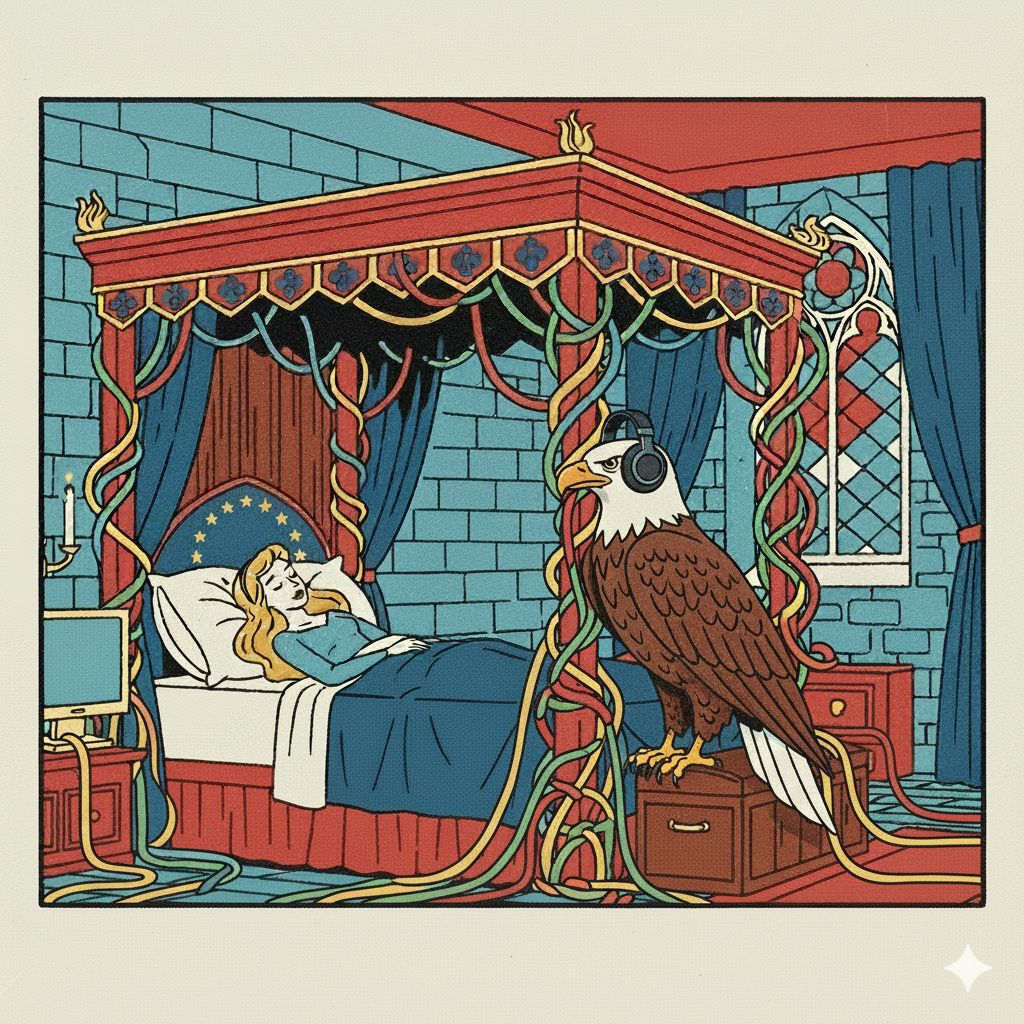

Transit point 1: Hardware and OS

This transit point is the physical reality of your digital life: the laptop on your desk, the server in the rack, and the Operating System that is running it. While we often worry about the security of the cloud, we frequently forget that “the Cloud is just somebody else’s computer”, and almost every computer in Europe is built on American intellectual property.

The chips

Within the hardware the chips and the semiconductors like silicon where it is made from are the most crucial element in relation to US access ability. The vulnerability starts deep inside the silicon. Modern processors from US companies like Intel and AMD are not simply calculators; they contain a “computer within a computer.” Components like the Intel Management Engine (CSME) operate at a privilege level deeper than the operating system itself.

This subsystem has full access to the computer’s memory and network, running even when the device is seemingly turned off. While the US government forces manufacturers to disable this “black box” for their own high-security agencies, European businesses are left with these features active, creating a permanent, unfixable potential backdoor.

For servers, the risk is even more acute due to the Baseboard Management Controller (BMC). This tiny chip on the motherboard allows administrators to remotely reinstall operating systems, install or modify apps, and make configuration changes to large numbers of servers and even without the servers being turned on. Normally, administrators use this BMS only to perform necessary maintenance operations, but it can also be misused by hackers or under compulsion from a government authority.

However, the proprietary firmware that runs these chips is controlled by US vendors. If a vendor is compelled by a FISA order to push a malicious update to the BMC, US authorities could theoretically gain “God Mode” access to European data centers, capable of copying or deleting entire hard drives without the main operating system ever detecting an intrusion.

Chips trade

The global supply chain for chips effectively functions as a fragile triangle where the United States holds the intellectual reins. The “brains” of the computer, the CPU and GPU, are designed by American giants like Intel, AMD, and NVIDIA. This means the architecture itself contains US-mandated features, such as the Intel Management Engine discussed above, and is entirely subject to US export controls.

Manufacturing introduces a different kind of volatility. Because the actual fabrication of these chips happens mostly at TSMC in Taiwan, the entire system is exposed to a massive control risk. If geopolitical tensions in the Taiwan Strait were to escalate, or if the US pressured Taiwan to cut off supplies to specific regions, the flow of advanced chips could stop instantly.

This risk is even more acute with the rise of AI, where NVIDIA currently holds the keys to the future. It has a share of more then 80% in the global share for GPUs for AI compute. The US government already restricts who NVIDIA can sell its top-tier chips to, meaning that if a European industry falls out of favor in Washington, it could be denied the hardware necessary to compete in the global AI race.

Europe finds itself in a particularly paradoxical position regarding this supply chain. The Dutch company ASML is arguably the most important tech company in the world, building the lithography machines that make all advanced chips possible. Theoretically, this should give Europe massive leverage, but the reality is that the US government effectively dictates ASML’s export policy. Through mechanisms like the “Foreign Direct Product Rule”,

Washington successfully forced the Netherlands to stop selling machines to China, proving that even when Europe makes the machine, the US decides where it goes.

Operating systems

Hardware is of limited use without operating software, and in this area US firms remain dominant. Microsoft Windows and Apple macOS control most of the desktop market, while Google and Apple dominate mobile operating systems. These platforms are not passive tools but incorporate extensive telemetry by design. As the Dutch government highlighted in its Data Protection Impact Assessment of Windows (see example 2 below), such systems can transmit usage data, filenames, and behavioral information to servers under US jurisdiction, and users have limited practical ability to fully opt out of these mechanisms.

Auxiliary Hardware components and their firmware

Beyond the operating system, modern computers contain multiple auxiliary hardware components that run their own firmware and operate largely outside the user’s control. These include management controllers, embedded processors, network interfaces, and firmware such as UEFI and BIOS. Many of these components are developed by US based companies and are subject to US jurisdiction. Because they function below the operating system layer, they can theoretically provide access to system state, memory, or network traffic even when the main OS is hardened or replaced.

While there is no public evidence of routine mass surveillance, the existence of such mechanisms creates a structural risk. Under US law, companies can be compelled to provide access under secrecy orders, raising concerns that software control alone may not be enough to prevent foreign legal or intelligence access in complex hardware systems.

In 2017, WikiLeaks published a large archive of classified CIA documents known as Vault 7. These describe tools and malware that can persist on devices, including techniques to modify firmware and make persistence below the OS layer (for example, implants on Mac firmware and other low-level components that survive operating system reinstalls). The leaks do not prove these tools were broadly used against U.S. companies’ hardware, but they do show design and capability for firmware-level access.

There are no public, fully authenticated cases where the U.S. government used embedded firmware backdoors in commercial hardware to access user or company data. Intelligence capabilities such as those revealed in the Vault 7 leaks do show that agencies have developed firmware-level techniques to persistently access devices (not supported by government admissions). These disclosures support the theoretical risk that hardware below the OS is a potential vector for surveillance and access.

European alternatives

While this is the hardest transit point to make European, cracks in the monopoly are forming. Europe currently lacks a direct competitor to Intel or NVIDIA, although long term initiatives such as the European Processor Initiative and the open RISC V architecture aim to support the development of more sovereign chip designs. In the meantime, niche European companies like Germany’s Tuxedo Computers or the Netherlands based Fairphone demonstrate that hardware can be built with greater supply chain transparency, even though they still rely on foreign manufactured silicon.

The EU Chips Act and the Dresden Expansion

To secure its digital sovereignty and stabilize the hardware layer of the internet, the European Union has launched the EU Chips Act, a ambitious €43 billion framework designed to double Europe’s global semiconductor market share to 20% by 2030.

A cornerstone of this initiative is the ESMC (European Semiconductor Manufacturing Company) fabrication plant in Dresden, Germany. This is a joint venture led by TSMC (the world’s largest chipmaker) in partnership with Bosch, Infineon, and NXP. This €10 billion facility represents a massive shift toward domestic high-end manufacturing, specifically targeting the chips required for automotive, industrial, and network infrastructure.

However, building factories is only half the battle. Europe remains critically dependent on foreign markets for critical raw materials such as gallium, germanium, and rare earth elements, which are essential for semiconductor production. Currently, Europe produces very few of these materials internally, with China controlling over 80% of the global supply for several key elements. This creates a “bottleneck” vulnerability: even with the most advanced factories in Dresden, the European hardware layer remains susceptible to export original restrictions and supply chain shocks from abroad. To address this, the EU is concurrently pushing the Critical Raw Materials Act to diversify sourcing and encourage domestic mining and recycling. Part of this Act, to mitigate the dependency risks, the EU also launched the RESourceEU Action Plan in December 2025, which aims to mobilize €3 billion to support alternative supply projects and recycling efforts beginning in early 2026

Operating System alternatives

For businesses, one of the fastest ways to reduce operating system level telemetry is to migrate to Linux distributions such as SUSE or Debian, which offer greater transparency and control over data flows. For governments and operators of critical infrastructure, reducing dependence on proprietary operating systems subject to foreign jurisdictions is increasingly seen as a key step in limiting exposure to external legal and political pressures.

Examples transit point 1

Two examples illustrating how the U.S. government has exerted influence over this transit point 1 in the past.

Example 1 - Intel chips Management Engine, a backdoor?

For over a decade, security experts have warned that the Intel Management Engine (a tiny, separate computer physically built inside your main processor) could function as an, undetectable spy tool. While Intel historically claimed that this subsystem was essential and could not be disabled, that narrative collapsed in 2017. Researchers discovered a hidden “kill switch” buried deep within the chip’s code labeled the “High Assurance Platform” (HAP) bit. This undocumented switch was designed specifically for the NSA, proving that the US government forces manufacturers to disable surveillance features for their own high-security agencies while leaving them active for everyone else. It got widely seen as a security hazard, with advices how to turn it off.

Silicon-as-a-Service

Today, this technology has been rebranded as the Intel Converged Security and Management Engine (CSME), but a new, more direct control mechanism has emerged known as “Intel On Demand”. This model introduces “Silicon-as-a-Service,” where the processor contains powerful built-in accelerators that are physically present but locked by software. To access the full power of the hardware you purchased, you must download a cryptographically signed license certificate from Intel.

This architecture creates a structural dependency on proprietary firmware and feature-enablement mechanisms that are designed, controlled, and updated by a US-based vendor. Certain advanced capabilities are enabled or configured through vendor-controlled firmware, microcode, and provisioning processes that customers cannot independently audit or replicate.

While there is no public evidence that Intel systems require continuous contact with external licensing servers to maintain normal operation, this model concentrates control over critical functionality outside the physical and legal jurisdiction of the data center operator. In a sanctions or export-control scenario (such as those applied by the United States to companies like Huawei or Kaspersky) governments have demonstrated their ability to legally restrict the sale, support, or provisioning of technology by domestic vendors.

As a result, future access to firmware updates, feature enablement, replacement parts, or accelerator functionality could be limited or withdrawn through legal or contractual mechanisms rather than technical failure. Such restrictions would not necessarily power down existing servers, but they could prevent the use or renewal of specific capabilities relied upon by high-performance workloads, including AI acceleration or cryptographic offload, potentially forcing operators to degrade services or redesign systems under time pressure.

This represents not a proven “kill switch,” but a geopolitical and supply-chain risk inherent in deeply integrated, proprietary hardware platforms whose trust anchors and update authority remain external to the deploying organization.

Example 2 - Dutch DPIA’s and European audits on M365 and Windows OS

A notable example of regulatory scrutiny at the operating-system and application level comes from a series of Data Protection Impact Assessments (DPIAs) commissioned by the Dutch Ministry of Justice and Security. Starting in 2018, the Dutch government evaluated the data protection risks associated with products such as Microsoft Office 365 ProPlus and Windows 10/11 Enterprise, producing public assessments of how these products collect and process usage and diagnostic data. These DPIAs included analysis of telemetry data flows from Dutch public sector deployments to infrastructure outside the European Union.

The DPIAs identified issues related to the transfer and processing of usage and telemetry data outside the EU, which were considered significant enough to warrant contractual and technical mitigation measures negotiated with Microsoft. These assessments prompted the Dutch government to work with Microsoft to improve transparency, data-handling options, and compliance with the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

At the EU-wide level, the European Data Protection Supervisor (EDPS) ( the independent watchdog responsible for EU institutions’ compliance with data protection law) found in March 2024 that the European Commission’s use of Microsoft 365 did not fully meet the requirements of EU data protection regulation. The EDPS’s decision concluded that the Commission had failed to ensure adequate safeguards for personal data transferred outside the EU/EEA and had not sufficiently specified data processing purposes in contractual arrangements with Microsoft.

Following the EDPS decision, the Commission was ordered to suspend certain data flows and bring its use of Microsoft 365 into compliance with EU rules by late 2024. In July 2025, the EDPS concluded that the Commission had implemented contractual and organisational changes that addressed those infringements.

These developments illustrate the data protection and sovereignty challenges that can arise when widely deployed operating systems and productivity suites (even at the highest enterprise level) collect and transmit user data across jurisdictions. They have raised broader concerns in Europe about dependency on software stacks developed and operated under non-EU legal regimes, particularly where personal or sensitive data may be subject to outside access under foreign legislation such as the U.S. CLOUD Act.

Within this act the American government can still compel U.S.-based providers to disclose data held by European subsidiaries, regardless of any private agreement or the client’s status. While companies can challenge these orders, the process is discretionary, leaving data legally vulnerable to foreign intervention despite the appearance of compliance.

This situation highlights a recurring regulatory impasse: contractual safeguards cannot fully neutralize the extraterritorial reach of U.S. surveillance law. The EDPS’s 2025 resolution appears to have been a pragmatic accommodation rather than a definitive technical solution, avoiding measures that could have effectively excluded U.S. providers and disrupted the functioning of European institutions.

For European organizations, the broader lesson remains that the “legal firewalls” offered by American hyperscalers provide, at best, limited protection. Digital sovereignty cannot be achieved through ever more complex contractual arrangements alone, but requires structural independence, including hosting critical data and systems on infrastructure that remains outside foreign jurisdictional control.